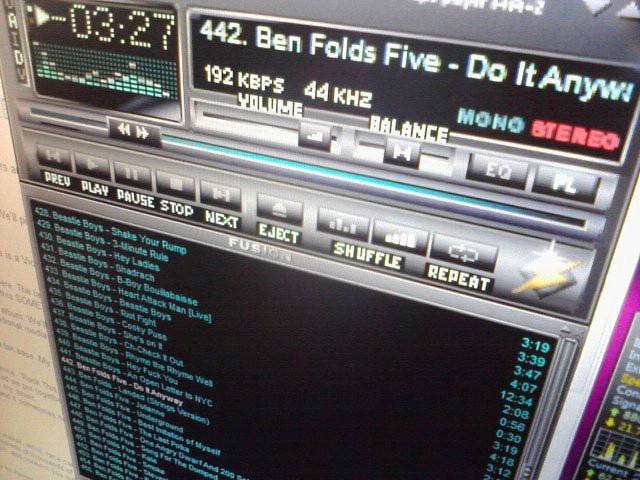

MP3s are so natural to the Internet now that it’s almost hard to imagine a time before high-quality compressed music. But there was such a time—and even after "MP3" entered the mainstream, organizing, ripping, and playing back one's music collection remained a clunky and frustrating experience.

Enter Winamp, the skin-able, customizable MP3 player that "really whips the llama's ass." In the late 1990s, every music geek had a copy; llama-whipping had gone global, and the big-money acquisition offers quickly followed. AOL famously acquired the company in June 1999 for $80-$100 million—and Winamp almost immediately lost its innovative edge.

Winamp's 15-year anniversary is now upon us, with little fanfare. It’s almost as if the Internet has forgotten about the upstart with the odd slogan that looked at one time like it would be the company to revolutionize digital music. It certainly had the opportunity.

“There's no reason that Winamp couldn’t be in the position that iTunes is in today if not for a few layers of mismanagement by AOL that started immediately upon acquisition,” Rob Lord, the first general manager of Winamp, and its first-ever hire, told Ars.

Justin Frankel, Winamp's primary developer, seems to concur in an interview he gave to BetaNews. (He declined to be interviewed for this article.) “I'm always hoping that they will come around and realize that they're killing [Winamp] and find a better way, but AOL always seems too bogged down with all of their internal politics to get anything done,” he said.

The problems began early, since Nullsoft wasn't interested in being a traditional corporate unit. For instance, in 2000, just a year after the acquisition, Frankel released (and open sourced) Gnutella, a new “headless” peer-to-peer file-sharing protocol that understandably steamed the bigwigs at AOL corporate headquarters in Dulles, Virginia.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...